September 21st could be thought of as the birthday of Mormonism.

For nearly two centuries stories have been circulated about events that millions of people around the world believe took place on Sunday night, September 21, 1823 in a small log home near Palmyra, New York.

The first stories were told among members of Joseph and Lucy Mack Smith’s family. Within two years, some details of those stories leaked out and were circulated among certain neighbors of the Smiths. Over the next few years, rumor, speculation, superstition and religious enthusiasm led to the telling of conflicting stories—some greeted as evidence of Divine intervention in human history, some seen as omens of darker supernatural powers at work, and others cited as proof of a great fraud being perpetrated on the gullible.

In the confusing swirl of conflicting stories about the events of September 21, 1823, a new religious tradition was born that quickly grew beyond the expectations of most people. As that movement spread beyond upstate New York into Ohio, Missouri and Illinois, its leaders tried to bring clarity to the chaotic stew from which their faith sprang. In short, they tried to create an official origin story for their religion.

They made several attempts. In each of these origin stories, details were added that conflicted with those found in earlier versions but which supported recent innovations in the faith’s theology and organizational structure. Each of these later retellings became more miraculous and majestic—presenting a cosmic struggle between the forces of Divine goodness and Satanic evil. When the movement splintered into competing denominations in the late1840’s, some relegated these later stories to history books while others canonized them as scripture.

Reform Mormons tend to think that greater spiritual value is found not in trying to prove or disprove the historicity of these later “official” histories, but in returning to the earlier versions of the story—the ones closer in time to 1823—and looking for the elements of those stories that might speak to the spiritual concerns of people living today.

One of the earliest detailed accounts of Sunday night, September 21, 1823, was written by Mormonism’s co-founder, Oliver Cowdery in a letter dated September 7, 1834--and published in the October 1834 issue of “Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate.”

Oliver wrote that on that the night of September 21, 1823, teenage Joseph Smith was not even sure if God existed. The teenager called “upon the Lord in secret” for an answer to the question: “If a Supreme Being did exist, to have an assurance that he was accepted of him.”

To understand why 17-year-old Joseph Smith doubted the existence of God, one needn’t look any farther than his parents. His father, Joseph Smith Senior, was a Universalist who rejected any theology that relegated any portion of humanity to a burning Hell for all eternity. Joseph Senior has no use for organized religion, and expressed his spirituality in terms of folklore and folk magic. In contrast, young Joseph’s mother Lucy Mack Smith embraced a more Calvinistic faith: she was deeply afraid that she, her husband and children might face eternal damnation—that they needed to secure their Christian salvation. The religious differences between Joseph Smith’s parents were profound, and they undermined any sense of unity and stability in the life of the family. It does not take much effort to imagine that discussions of religious differences in the Smith household might have easily escalated into powerful arguments that could have caused the teenage Joseph to be critical of religion generally and of traditional notions of God specifically.

According to Oliver, the teenage Joseph Smith “was unusually wrought up on the subject that had so long agitated his mind—his heart was drawn out in fervent prayer, and his soul was so lost to everything of a temporal nature, that earth had lost its charms, and all he desired was to be prepared in heart to commune with some kind of messenger who could communicate to him the desired information of his acceptance with God.”

Oliver Cowdery wrote that near midnight, after Joseph’s brothers had fallen asleep, “while continuing to prayer for a manifestation, on a sudden a light like that of day, only of a purer and far more glorious appearance and brightness, burst into the room.” Joseph later told Oliver that it seemed to him “as though the house was filled with consuming and unquenchable fire.” At first the appearance of such luminous splendor “occasioned a shock or sensation, visible to the extremities of the body,” but that was soon followed by a “calmness and serenity of mind, and an overwhelming rapture of joy that surpassed understanding.”

In a moment, a personage stood before Joseph floating in mid-air. Although the room had previously been filled with light, Oliver wrote, there seemed to be an “additional glory surrounding or accompanying the personage, which shone with an increased degree of brilliancy.” Though the countenance of the messenger was “as lightening,” it was of such a “pleasant, innocent and glorious appearance,” that all fear was banished from the boy’s heart and “nothing but calmness pervaded Joseph’s soul.”

The turning point in Cowdery’s story comes when Joseph, laying in his bed and wondering if God even exists, desires to know if the God—whose existence he questions—finds him acceptable.

How many people find themselves in that situation? Raised in a particular faith, they find themselves unsure of everything they were taught to believe—even the existence of God. And yet, at the same time, though unsure if God does exist, they still want to know that they are loved and accepted if God does exist.

According to Oliver’s account, while Joseph was in the midst of this conflicted state of mind, light began filling the room, bringing with it a calm and a glory that banished all fears. This sets into motion miraculous events which three years later leads to a new book of scripture and the opening of the scriptural cannon.

According to various stories told about the coming forth of that new scripture, for the next four years (1824, 1825, 1826 and 1827) September 21st became a day for Joseph Smith to re-evaluate the previous year of his life, to meditate on lessons learned, to repent and prepare for the future he felt God had in store for him. In this way, it was similar to the High Holy Days in Judaism—which coincidentally takes place every year during this same week in September. The process of honestly accessing one’s life and spiritual state, of accepting doubts, repenting of sins is essential in order to prepare for the revelation of further Light in our lives.

And so, on the night of September 21st, Reform Mormons try to take a deeper look at where they are relative to their spiritual and ethical progression. They contemplate the events of the previous year and what might be in the year to come. If they have doubts about God—or any other belief or idea related to their faith—they try to confront these doubts openly, honestly and with integrity. Just as one needn’t stay married to one’s current beliefs, one needn’t be divorced from one’s doubts. Beliefs and doubts can both fuel one’s Eternal Progression. The goal is not to get to somewhere else by virtue of believing “the right things,” but to become the type of human being whose personifies the Divine. Accepting doubts, being able to live with ambiguity, repenting of those things that we honestly, within ourselves, believe are wrong (as opposed to those things that traditions, institutions and others insist are wrong)—being able to do all of these things may not only bring a profound sense of peace, they can also open our eyes to the Light that will lead us into the future.

Thursday, September 21, 2017

Monday, September 11, 2017

REMEMBERING 9/11 ... 1857

Can a community born of faith in the loftiest of ideals, descend into hatred, intolerance, murder and terror? Can a people who embraced a prophetic tradition—who gathered together because they were keenly aware of the injustice, hard heartedness and self-righteousness in the world become so zealous that they move beyond merely embodying the attitudes that they once decried, to embracing barbarism?

The answer is yes, and no people should be more aware of that truth than those belonging to the Mormon religious tradition. Mormonism is, after all, a tradition that originally sprang from the embrace of “The Book of Mormon.” Before the earliest believers had any fully formed explanation of the book’s origins, they had in their hands the book itself. That book told a story that spoke to their experiences and reflected their understanding of human nature and the world in which they lived.

“The Book of Mormon” told the story of two ancient peoples—both descended from a prophet who saw the corruption of the society in which he lived, and fled with his wife and children to a distant land. There, separated from his kinsmen, the prophet hoped that his children and their descendants would live as a free, just, godly and virtuous people. But from the beginning of the story, all of his children engaged in violence, jealously and division.

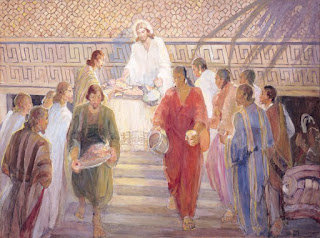

The prophet’s descendants divided themselves into two distinct civilizations—neither of which were purely just or virtuous, and both of which embraced violence and war when they felt threatened. In each of these two cultures there arose divinely-called prophets and leaders—and in each, there arose charlatans, demagogues, war-mongers and tyrants. For six hundred years, these two cultures not only warred with one another, but were each internally divided ethnically, religiously and politically. Each cultural was blinded by the belief that its enmity with the other was either rationally or divinely justified. Brought to the brink of destruction not only by violence but by catastrophic natural disasters at the time of Jesus’s crucifixion, they were visited by the resurrected Christ who taught them the principles embodied in the Biblical Sermon on the Mount. After six centuries of ethnic division, demagogy, social injustice and war, the two civilizations come together as one people and lived in peace for over a century. The reason for—and the key to—this lasting peace were the pure and simple principles taught by Jesus: love your enemy, pray for those who despitefully use you, turn the other cheek, bless those who curse you, go the extra mile, bear one another's burdens, avoid being sanctimonious.

After a century, prosperity, pride, self-righteousness and contentiousness took root within the people. Ancient grievances were revived, and people divided themselves along ethnic lines. Both descended into barbarism, with one civilization becoming even more sadistic than the other. That civilization—which, through most the story, had the stronger prophetic tradition—was eventually annihilated by the other.

“The Book of Mormon” was cautionary tale for the people who first read it—first and second-generation Americans who were still insecure with the personal liberties their newly formed Republic guaranteed them. These first readers were cautious regarding potential abuses of power by civic as well as ecclesiastical authorities and institutions. They embraced the “pure and simple Gospel of Christ”—which could best be summarized as putting love and charity above all else.

It is one of the supreme ironies in American history, that the largest community of Mormons would, in the 1840s, as a result of persecution and political intrigue, leave the United States, settle in the Rocky Mountains and desert southwest, and there turn inward on itself—instituting an internal “reformation” in which the choice was either unquestioning obedience to ecclesiastical authorities, or punishment—including death (so-called “Blood Atonement”) for blasphemy and apostacy. The theocratic government established in Utah Territory bought its Mormon population in direct conflict with the principles of the United States Constitution. It was soon assumed that military conflict between Utah territorial militias and Federal troops was inevitable.

During this period—in the late summer of 1857—a wagon train made up of Americans primarily from Arkansas and Missouri was making its way to California, through southern Utah. Twenty-five years earlier, Missouri had been the central gathering place for Mormons, but religious persecutions there had ended with a massacre of Mormons at a settlement called Haun’s Mil, and an extermination notice signed by the Governor of Missouri—the only such order ever issued by a U.S. governor against U.S. citizens. The memories of those persecutions and the resentments had only festered among the Mormons seeking to pioneer the harsh desert southwest. The California-bound wagon train wandered into what could now be described as a “perfect storm” for tragedy.

Led by the Mormon Priesthood High Council of Cedar City, Utah, the local militia attacked the wagon train in a spot called Mountain Meadows. After a conflict lasting several days, on September 11, 1857, the wagon train surrendered to the militia after being assured that they would be escorted to safety. Having given up their weapons, the men, women and children of the wagon train formed a long line and, escorted by Mormon militia men, they began to walk out of Mountain Meadows. Suddenly given the signal, each Mormon militia man turned on the man, woman or child nearest him. Within minutes, over 100 men, women and children—aged 8 and older—lay massacred in Mountain Meadows. Their mutilated bodies were left unburied for weeks.

This event—the Mountain Meadows Massacre—was the worst case of domestic terrorism in U.S. history until the Oklahoma City Bombing in 1995. What is so tragic and ironic, is that the perpetrators of the massacre were themselves the victims of earlier religious persecutions and massacre.

Perhaps the greatest irony is that the worst act of domestic terrorism in U.S. history would be perpetrated on September 11, 2001—144 years to the day since the Mountain Meadows Massacre. As with the terrorism of 9/11/1857, the terrorism of 9/11/2001 was perpetrated by religious zealots who clung to memories of and resentments regarding earlier persecutions that their religious communities had suffered.

Reform Mormons embrace 9/11 as a Day of Remembrance. The two terrorist acts that took place on this day—in 2001 and in 1857—are taken as warnings of what can happen when a community clings to grievances of past wrongs, and assumes that they have either a rational or a divinely-mandated license to avenge those wrongs.

Reform Mormons turn to the story told by “The Book of Mormon” for guidance. They realize that no community is immune to bitterness, to fantasies of vengeance for wrongs suffered, and to the intoxicating but deadly illusion that violence against one’s enemies is divinely sanctioned.

On 9/11, Reform Mormons seek to remember that despite wrongs and injustices suffered, they have committed themselves to emulating the character of God as revealed in the character of Jesus. That character is embodied in the principles found in Biblical Sermon on the Mount and in “The Book of Mormon’s” Sermon at the Nephite Temple:

“Behold, it is written, an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth;

but I say unto you, that ye shall not resist evil.

Whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other…

Love your enemies, bless them that curse you,

so good to them that hate you,

and pray for them who despitefully use you and persecute you;

that ye may be the children of your Father who is in heaven;

for He makes his sun to rise on the evil and on the good…

Old things are done away with, and all things have become new.

Therefore, I would that ye should be perfect even as I, or your Father who is in heaven is perfect."

(See III Nephi 12: 38—48 [LDS Edition] / III Nephi 6: 84—92 [COC Authorized Version]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)